Why Would Someone Buy Bespoke Shoes? We Asked a Master Shoemaker

For most people, custom footwear lives somewhere between fantasy and mystery. It’s hard to picture what the process actually looks like, or why anyone in the 21st century would choose to buy shoes in such a slow and expensive way.

So I went to Brooklyn to meet with master shoemaker Francis Waplinger, who makes bespoke footwear right here in the city.

For this visit, I brought along my friend David Thomas Tao, a local whiskey journalist and theater producer who is always going to the sort of fancy events for which one might buy the fanciest shoes possible.

I think inviting David gave the interview a balanced perspective: I spent all my time talking about shoes, while David represents the everyday customer who isn’t sure what all the hubbub is about.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

The Bespoke Timeline

David: How do people usually find you? Do you advertise much?

Francis: Most clients find me through interviews like this — YouTube, Instagram, podcasts, and online publications.

David: Would you mind taking us through the timeline when a new client comes to you? Looking at your website, it’s a pretty lengthy timeline — it surprised me at first — but the more I read and the more I learn, it makes sense that it could be a 14- to 16-month timeline to get everything dialed in and get the shoes made.

Francis: The process starts generally by appointment. A new client comes in, I measure their feet first, then we’ll go over what they’re looking for — design, leather choice, toe shape. I’ll have a conversation: what’s in their wardrobe? Is this an “everyday” shoe they’re going to be wearing? Is it for an occasion? We set that up and select the design and leathers.

After that, it’s on average two to three fittings. From there, we make the last — the foot-shaped mold that dictates the fit and which I customize to their foot — and I build “fitting shoes” on the last. That’s something of a “test shoe” that’s just to check the fit. On average, there are two to three fittings before I move onto making the shoe itself.

Once they’re happy, and I’m on the same page with them, and I think the fit’s good, then I go to the final shoe.

There’s a lot of work in that. Every client, I create a pattern and last just for them.

Further Reading

The Ultimate Guide to How Boots Should Fit (5 Areas to Look At)

We asked Weston Kay from RoseAnvil and Dr. Neal Blitz, a foot surgeon, how to get the best boot fit. Learn more →

David: If they come back for a second pair, is the timeline much shorter?

Francis: I’m doing my best to keep it lower. I’m going to say six to twelve months for the return customer who already has a last made. I’m trying to get the upper limit down to eight months.

It is a pretty long timeframe, to be sure. I’m trying to get a first pair down to a year, but it’s still going to take time to chip away at existing orders. I’m trying not to make shortcuts.

Infinite Choices: How to Help Clients Decide On a Shoe

David: What if a client has no idea what they want?

Francis: I’d ask: is it an everyday shoe? Is it something you’ll wear multiple times a week? What’s in your wardrobe? What are you going to wear with the shoes?

If you have all black suits, let’s go all black. If you wear a lot of denim, maybe you want a chukka boot. Is it suits, casual, blazer, how dressy, how casual — that gives me a hint.

Usually, once I show a few leathers, people land on a couple. It helps when people know what they don’t want. Then we piece it together into something they feel comfortable with.

David: It’s almost like getting a tattoo. There can be—like—you can just say, “I want something like this,” or “I want something inspired by this,” or it can be a super collaborative process. It’s art.

Francis: Yes, and you need to know the difference between what you like the look of and what you’ll actually want to wear. As a maker, I’ve made the mistake of getting really excited about leathers and color combinations that ultimately don’t work that well. For example, when I first came back from Italy, I was super excited about chisel toes. I did a burgundy suede, light brown shoe, made it, loved it, and then I realized it went with nothing in my closet. I still wore the hell out of them, but it was a learning experience.

Bespoke vs Custom vs Handmade vs Handcrafted

David: There are four terms that I hear thrown out a lot, and I’m trying to wrap my head around the differences: bespoke, handmade, handcrafted, and custom. Can you run us through what a bespoke shoe truly is, and how that differs from the other terms?

Francis: When I think of bespoke footwear, I’m thinking of a shoe built just for your feet, for the measurements of your feet. It’s built on your personal last.

As for handmade versus handcrafted, those terms are broad and to me, they’re used pretty interchangeably. I’d say handmade is a vague term that exists on something of a spectrum: many shoes are made with a lot of machines, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t still a lot of manual work involved.

When a shoe is bespoke, though, it’s usually handmade to a very high degree. Hand-lasting, hand welting, the sole is stitched on by hand.

With that said, you could have a bespoke shoe made to your measurements with more machine work in it. It could still be bespoke because the main thing with bespoke is really the fit: that you’ve invested in getting a last made for your foot.

Most bespoke makers, including me, still use machines for certain steps, like stitching uppers. It’s more of a spectrum than a strict definition.

Custom, on the other hand, usually means standard sizing, but the client chooses details like leather, color, or design elements.

Further Reading

Hand Lasted Boots: Overhyped or Underappreciated?

Does “handmade” really mean a better boot? We spoke to five different bootmakers to get you the facts.

Learn more →

What Makes a Shoe Feel “New York”?

SW: What informed the way you design your shoes? I understand you learned in Italy before coming back to the U.S., and you mixed two different design philosophies.

Francis: Yes, I was trained in Italy. So how I approach shoes — construction, patterning, making — it’s very Italian.

When I came back to the U.S., I felt very Italian — but I’m not. I was born and raised in the U.S., and I’m in New York City. So I was thinking about the romance of New York City and the romance of old, vintage American styles from the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s.

I’m taking everything I learned in Italy and trying to create my own aesthetic, my own style inspired by New York City.

SW: How does a pair of shoes reflect New York?

Francis: Well, New York’s pretty famous for art deco. I like it when a building or design gives meaning to the time it’s in and the place. Like the Empire State Building — you know it’s unmistakably New York City, built in the early ’30s. Same with the Chrysler Building. You can identify time periods by architecture. Same thing all over the world. That’s the mentality.

So there’s not necessarily a specific design element I can point to on the shoe that’s inspired by New York City, it’s more that art deco is a concept that gets the creative juices flowing and that I keep in mind.

European vs American Fit, Aesthetics, and Foot Shapes

SW: What’s the difference between an Italian or European shoe and an American one? We’ve got the same feet, don’t we?

Francis: Yes and no. I’m painting with a broad stroke here, but there are slightly different foot shapes based on the country.

When I was in Italy, you see these slender Italian shoes — even ready-to-wear shops in Florence — and everyone wants that, but a lot of Americans just don’t like shoes that fit so close the bone.

That’s the beauty of bespoke: if someone wants a shoe to look a certain way, you can use design elements to create a beautiful elongated shoe while still fitting the foot, so you’re not jamming your foot in.

SW: That’s true, I think a lot of people don’t know that the shape of the average foot will often vary by country, especially in more ethnically homogenous countries.

For example, I was in Vietnam with Akito Boots, a small workshop not dissimilar to this one. The reason he became a shoemaker was that he couldn’t find shoes that fit Vietnamese feet very well — apparently, they tend to have high volume insteps and shorter toes — so he wanted more shoes shaped for that.

But there are also those aesthetic preferences you touched on. My European boots and loafers, especially from continental Europe, are all slim and tapered. Americans usually prefer rounder toes and roomier fits, and you see a lot of European brands struggle to understand that when they try to break into the American market.

Francis: Another big difference is how people like their shoes to fit. In Italy, a lot of Italians — and how I wear my shoes — is very snug. I lace my shoes tight; I like them snug.

When I came back and started making shoes, I was confused by this, but a lot of Americans like their shoes looser.

Francis: One thing that’s common in the States is a narrow heel but then a very wide forefoot.

It’s also not very common anymore for a brand to offer different shaped shoes for different customers. In the 30s, 40s, 50s, dress shoes would come in five different widths. No one does that anymore. In that sense, I’m filling a “fit void” that maybe wasn’t there.

SW: I’ve met a lot of guys who go their whole lives without knowing they’re a triple-E foot. They just think shoes are just supposed to feel like you’ve been jammed into them.

David: I remember when you told me those widths existed, and I went, “Wait a minute, I don’t need to be uncomfortable for the rest of my life.”

Favorite (and Least Favorite) Parts of Making Bespoke Shoes

David: What are your favorite and least favorite parts of the shoemaking process?

Francis: I really enjoy patterning. I enjoy the construction of the shoe. I enjoy finishing.

Last-making is always challenging, but I enjoy the challenge. It’s probably the least creative part, though, because you’re really looking at fit and angles and numbers — it has to be the most precise part of the process. It’s a little nerve-wracking when the client tries the fitting shoe on.

There are usually multiple fittings, but if I can do it in one fitting, that’s the best feeling. There’s pressure getting it right. It’s a puzzle. That’s how I describe it to clients. We’re dialing it in and in and in until the fit is correct.

Do Expensive Bespoke Shoes Last for Life?

David: Are these a lifelong investment?

Francis: It depends. They’re definitely an investment. They’re meant to be worn, meant to be repaired, meant to last a long time.

I’ll resole favorites two, three, and four times, and then they’re good for eight-plus years. Some clients bring in a shoe and say, “I’ve had this shoe for 30 years.” It finally wore out. So it’s a spectrum. It depends on how you maintain them and how often you wear them.

But if you have one pair of bespoke shoes and you wear them every day, no, they will not last a lifetime.

SW: I’m putting words in your mouth, but you’d probably tell people they shouldn’t wear the same pair every day, right? You’re supposed to give them a day to rest between wears and dry out.

Francis: That’s correct.

SW: Do you ever have the conversation where someone’s excited to get the most perfect, well made, individualized shoes they’ll ever buy, and then they can’t believe they’re not supposed to wear them every day?

Francis: I haven’t said that directly, but I hint at it. In the initial conversation, when I’m trying to figure out what they want, I’ll say, “You’ll be wearing these every few days.”

If they want to wear them every day, I won’t stop them. But yes, technically it’s good to rotate a few pairs.

The one thing I do say: when it snows in New York City, and you’ve got those salty lagoons at every street corner, please, please do not wear your shoes. I even bit the bullet and got a pair of L.L. Bean duck boots for those days. That salt will destroy leather.

Traditional Shoemaking, Non-Traditional Materials

SW: You like traditional shoemaking, but these days, more and more brands make shoes that are resoleable like old fashioned shoes, but they use modern, synthetic components like EVA foam, Poron, Texon, things like that.

Do you ever allow man-made materials in the construction of your shoes?

Francis: In the heel, under the sock liner, I can put a little foam if people’s heels are sensitive. That’s not uncommon for older customers.

But I like to keep the shoe as bare bones as possible. I don’t like to put tons of cushion in. There are certain foams, or you could do a foam midsole — that could be done — but I try to stay away from that. Usually, if they’re looking for that, they might not be looking for what I do. I try to stick to what I do.

I’ve had requests for vegan shoes. I was open to the idea, but I try to twist their arm a little bit, because vegan shoe is just plastic.

David: So you haven’t made that leap yet.

Francis: I don’t think I will. Part of the craftsman mentality is highlighting what the material is. “Vegan leather” is like an oxymoron in my mind.

If you want a vegan shoe that’s sustainable, use fabrics. It doesn’t have to look like leather and try to be leather. Use waxed canvas.

SW: Is there a material you haven’t worked with yet that you’re excited to try someday?

Francis: That’s a good question. I’ve worked with it minimally, but it’s always on my mind — I want to do a summer shoe that’s leather and canvas.

I have some old vintage canvas, and I did it for myself years ago, but I’d really like to go out and find a really nice canvas that’s durable and consistent. That’s one thing.

Francis’s Favorite Leathers

SW: What are the most common leathers you work with?

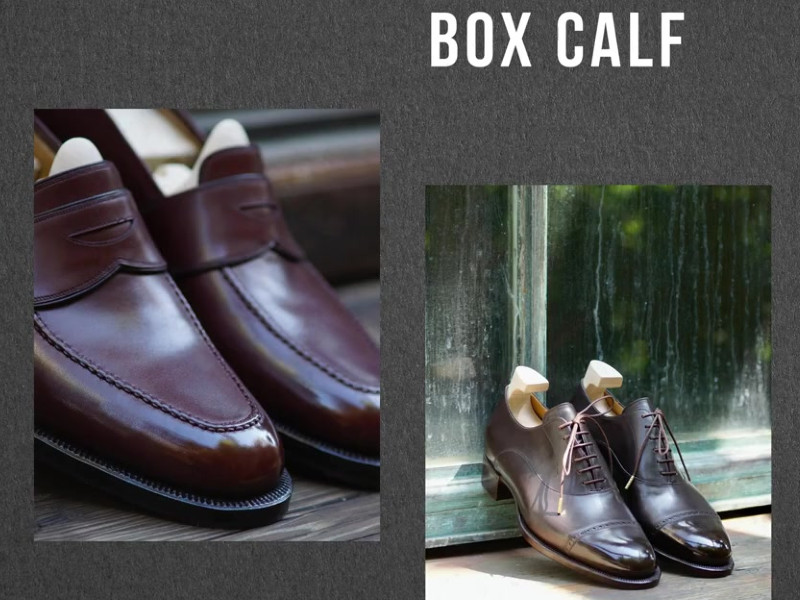

Francis: My favorite leather, and the one I work with most, is box calf or museum calf. The thickness, the feel, it’s classic dress shoe leather.

Box calf is basically a style and type of tannage. It’s semi-firm, fairly thin, and for me, very familiar. It’s easy to work with. You can polish it up, get that nice shine, and it has that traditional, classic look.

Museum calf is very similar; it handles the same, wears the same, but it has a little more movement in the grain. If you want something not too crazy, but with more character, it’s great. I really enjoy working with those.

Women’s Shoes and Design Differences

SW: Do you have many female customers?

Francis: I’d say maybe 20 percent of my customers are women.

The women’s shoes are similar to the men’s shoes, but there are some design elements you can use to make them more feminine. Most of my women’s samples are Chelsea boots, loafers, lace-ups.

Saying ‘No’ to Clients Without Being a Jerk

SW: Have you ever said no to a client’s design request?

Francis: I’ve had requests I just don’t do. I’ve had inquiries for sneakers — I don’t do that.

If someone wanted Western cowboy boots, I wouldn’t do that. I don’t do high heels for women. Those things just aren’t my specialty.

The longer I’ve been making, the more I try to stay true to my specialty and my style. There’s another shoemaker I know who said: If you want sushi, you go to a sushi restaurant. You don’t go to the pizza-hamburger-sushi restaurant.

SW: But you haven’t refused a request because you just think it would be too ugly? “I can’t create something so hideous.”

Francis: I don’t think I’ve had that.

David: I like your responses. They’re non-judgmental. You couch it as That’s not my specialty. I’m not the the person to take you on that journey. It’s very diplomatic — I’m stealing your answers for my personal life.

Francis: I try not to be judgmental. I definitely have my own opinions — I don’t think people should wear flip-flops unless they’re going to the beach — but I don’t force my opinions onto clients.

Advice for Aspiring Shoemakers

SW: What advice would you give to a young man or woman thinking about getting into shoemaking?

Francis: To learn the basics, I think you’re looking at three years minimum. Everything takes time.

When I came back from training, I underestimated how long it takes to build a cohesive collection. This is my third batch of samples — I’m constantly refining things, because you obviously need your offerings and your product photos to reflect what your aesthetic and design mentality is about.

The other main thing: there’s a big distinction between shoe making — hands-on, manual, physical — and shoe design. Some people might not realize they want to dod one and not the other. The best thing to do is take a one- or two-week short course and see which side you’re drawn to.

When I started, I did short courses before I went to Italy. I really enjoyed the hands-on making, and the design came secondarily.

Here in New York City, it’s much more fashion-centric and design-centric than “making-centric.” So the question is: do you want to be a shoe designer, a shoemaker, or a little of both?

SW: And get your feet wet with a week or two course before you dive into three years in Florence.

Francis: Yes, definitely take a short course if possible. When I took my course, a spark was lit, and I thought, “I want to make shoes. This is what I want to do.”

Find Francis at his website, on his Instagram, or at his workshop in Industry City, Brooklyn.